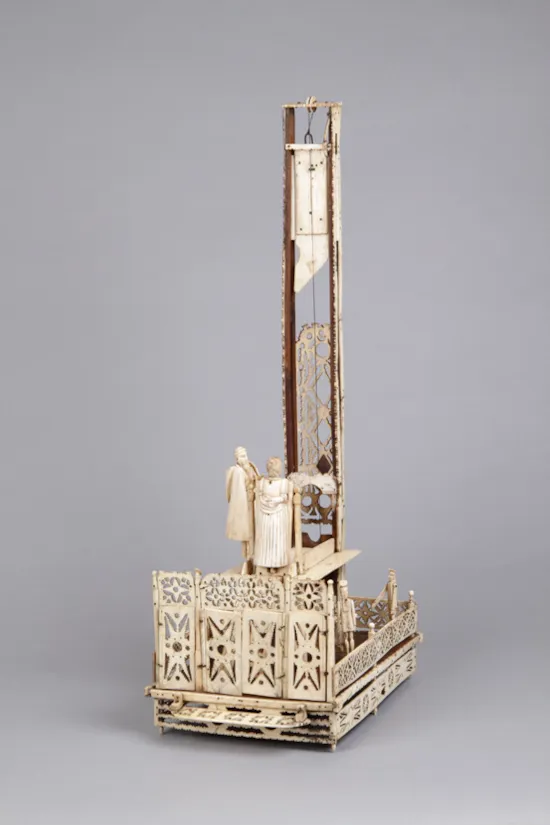

Large Napoleonic Prisoner of War Carved Bone Working Model of the French Revolutionary Guillotine

An Unusually Large Napoleonic Prisoner of War Carved Bone Working Model of the French Revolutionary Guillotine

The Recumbent Body of the Queen, Marie Antoinette, Lying on a Podium below the blade her decapitated head rolling into a waiting basket

A Priest by her side providing the last rites the waiting guards below with moveable arms

Late 18th – Early 19th Century

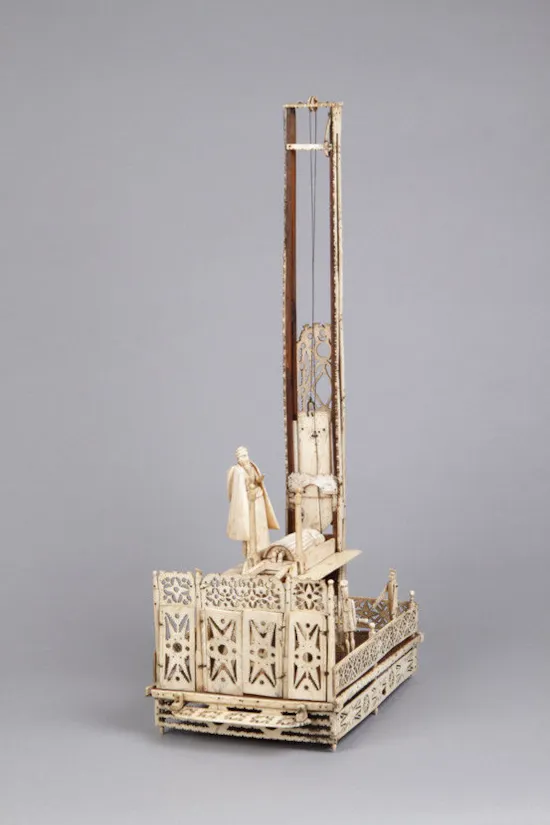

The Recumbent Body of the Queen, Marie Antoinette, Lying on a Podium below the blade her decapitated head rolling into a waiting basket

A Priest by her side providing the last rites the waiting guards below with moveable arms

Late 18th – Early 19th Century

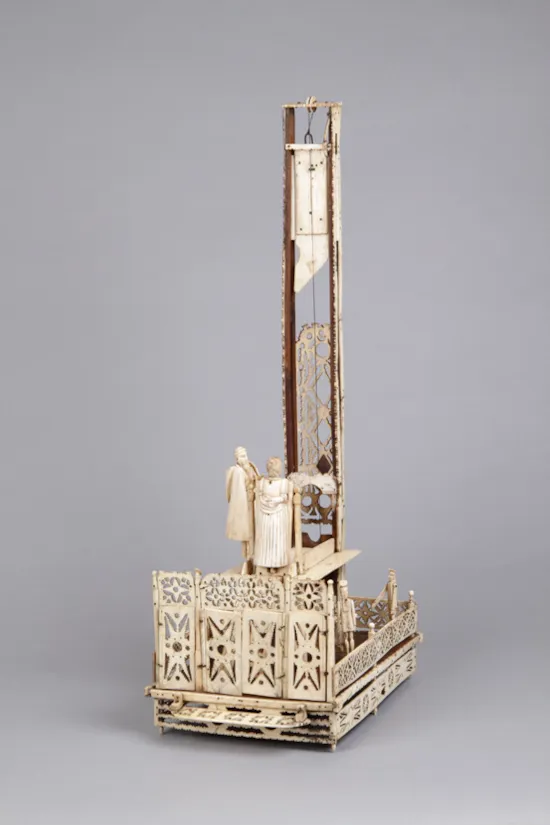

An Unusually Large Napoleonic Prisoner of War Carved Bone Working Model of the French Revolutionary Guillotine

The Recumbent Body of the Queen, Marie Antoinette, Lying on a Podium below the blade her decapitated head rolling into a waiting basket

A Priest by her side providing the last rites the waiting guards below with moveable arms

Late 18th – Early 19th Century

Size: 58.5cm high, 24cm deep, 19.5cm wide – 23 ins high, 9½ ins deep, 7¾ ins wide

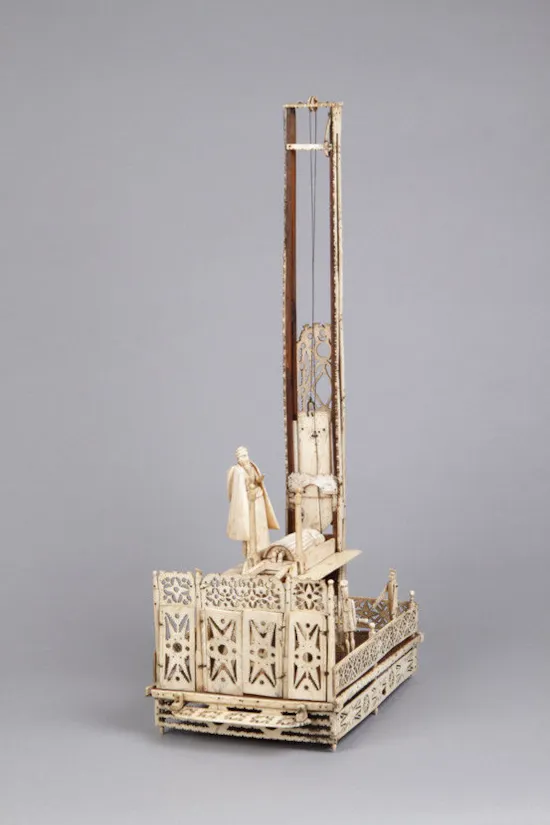

The Recumbent Body of the Queen, Marie Antoinette, Lying on a Podium below the blade her decapitated head rolling into a waiting basket

A Priest by her side providing the last rites the waiting guards below with moveable arms

Late 18th – Early 19th Century

Size: 58.5cm high, 24cm deep, 19.5cm wide – 23 ins high, 9½ ins deep, 7¾ ins wide

The guillotine, a device for swift execution, was invented by Joseph-Ignace Guillotin (1738-1814), a French physician and revolutionary. As Deputy, he proposed that the Constituent Assembly use a decapitating instrument. This proposal was adopted in 1791, and the machine was named after him.

During the Napoleonic Wars, over one hundred thousand prisoners were held captive in Britain. Many of these prisoners supplemented their meagre rations by selling objects carefully carved from the bones of their mutton stew. At Norman Cross near Peterborough, the camp kitchen cooked the stew in a cauldron that was five feet across and three feet deep. The bone would be collected and submerged in wet clay until it became pliable enough to use. Encouraged by the authorities, the prisoners formed artisan guilds and produced articles such as this guillotine, which they would sell in the civilian market held at the camp periodically. Occasionally, a particularly skilled artist would be privately commissioned to carve a work.

From 1796 to 1816, ten thousand men were held at the camp at Norman Cross near Peterborough. Many of these men learned English, some married local girls, and a few through making and selling products of their skill amassed small fortunes by the end of the war.

During the Napoleonic Wars, over one hundred thousand prisoners were held captive in Britain. Many of these prisoners supplemented their meagre rations by selling objects carefully carved from the bones of their mutton stew. At Norman Cross near Peterborough, the camp kitchen cooked the stew in a cauldron that was five feet across and three feet deep. The bone would be collected and submerged in wet clay until it became pliable enough to use. Encouraged by the authorities, the prisoners formed artisan guilds and produced articles such as this guillotine, which they would sell in the civilian market held at the camp periodically. Occasionally, a particularly skilled artist would be privately commissioned to carve a work.

From 1796 to 1816, ten thousand men were held at the camp at Norman Cross near Peterborough. Many of these men learned English, some married local girls, and a few through making and selling products of their skill amassed small fortunes by the end of the war.

Ex Finch and Co catalogue number 23, item number 62

Ex private collection

Ex private collection

Large Napoleonic Prisoner of War Carved Bone Working Model of the French Revolutionary Guillotine